Table of Contents

An adverse human rights impact occurs when an action removes or reduces the ability of an individual to enjoy his or her human rights.

When these impacts occur, they should subject to remediation. Remedy describes the process and the outcome that seek to restore human dignity. The focus on process means that remedy should be stakeholder-driven; the focus on outcomes seeks to counteract, or make good, the negative impact.

Forms of remedy

Remedy can take many forms, including:

- Apology (including acknowledgement of harm done)

- Restitution (restoring someone or something to its former condition prior to the harm or impact)

- Rehabilitation (facilitating someone’s recovery from harm, which may include medical or psychological care as well as legal and social services

- Compensation (including both monetary and non-monetary forms)

- Sanction (including contractual sanctions and penalties)

- Guarantees of non-repetition (including specific measures, mitigants, and activities to ensure that human rights abuses do not re-occur).

Effective remedy may require a holistic approach, including multiple elements from this list. Those affected should be meaningfully consulted about the type of remedy that would be appropriate and the manner in which it should be delivered.

Further reading

- UN Human Rights Access to Remedy in Cases of Business-Related Human Rights Abuse: An Interpretive GuidanceInterpretive guidance covering foundational principles relating to remedy as well as the establishment by businesses of effective operational level guidance mechanisms

- Working Group on Business and Human RightsAccess to remedyOverview of remedy principles as well as activities of the UN’s Working Group on Business and Human Right’s activities relating to remedy

The role of FIs in remedy

Financial institutions have a key role to play in remedy by deploying an ecosystem approach. This approach includes:

- Providing for and cooperating in remediation where FIs cause or contribute to adverse human rights impacts. Operational-level grievance mechanisms can be one effective means for proving remedy.

- Enabling remedy where FIs are directly linked to adverse human rights impacts. In such cases, they should use and build leverage in relation to clients / investee to enable remedy before and after harms have occurred.

According to the UN Human Right’s interpretive guidance on access to remedy, the term “remedy ecosystem” refers to the laws, policies, institutions, mechanisms and actors, and the relationships between them, that are relevant to whether or not people will receive remedies for human rights-related harm. It encompasses not only the rules, practices and procedures relevant to the functioning of specific judicial and non-judicial mechanisms, but also the background legal regimes (which may not necessarily be framed or understood in human rights terms) that are potentially relevant to whether an effective remedy can be delivered in specific cases.

For example, in addition to the various grievance mechanisms that may be available to affected stakeholders, actors such as banks, investors, or business partners may need to use their leverage with responsible parties to influence them to provide remedy.

Likewise, civil society advocates (including local or international NGOs or trade unions) who might help individuals or communities frame their complaints and support their effective participation in remedy processes would also be part of the remedy eco-system.

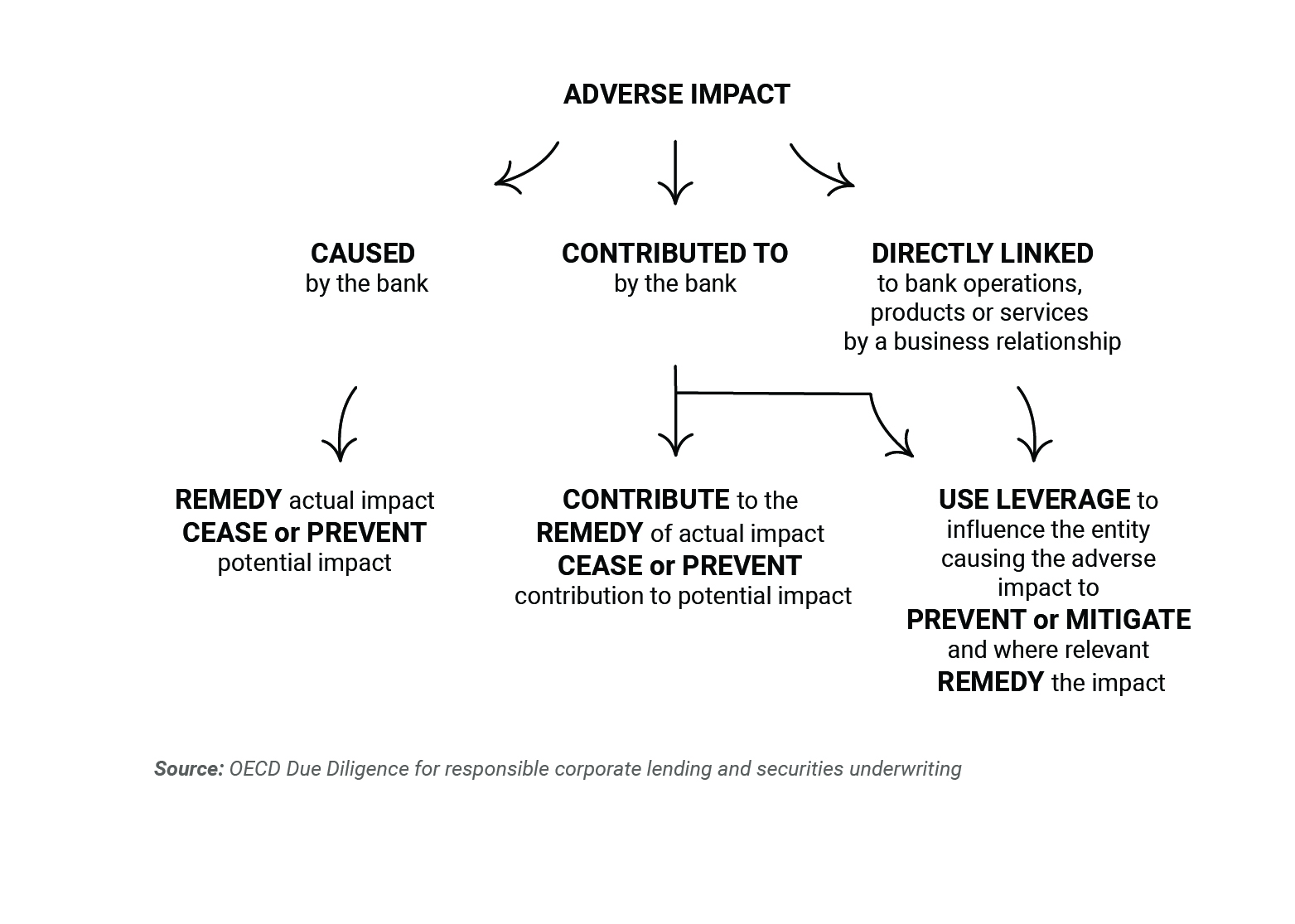

Under the UNGPs, FIs are expected to provide for – or cooperate in – the remediation of adverse impacts when they cause or contribute to those impacts. This is covered in more detail in the section on ‘Taking Action’ for both financing and own operations. Broadly, in cases where a financial institution is causing or contributing to actual adverse impacts it should take necessary steps to cease or prevent its own contribution, use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impacts to the greatest extent possible, and provide for or cooperate in the remediation of the impacts through legitimate processes. Where an FI is found to be directly linked to actual or potential adverse impacts related to a finance transaction, but has not contributed to the impact, it should use its leverage with clients (or project sponsors) to seek to prevent and mitigate the impacts, which can include encouraging remediation. Importantly, the FI’s relationship to harm is dynamic; it may change based on the situation as well as the level of due diligence measures undertaken.

Definitive guidance issued by UN Human Rights has clarified the factors that would influence how an FI is involved with an adverse human rights impact, as well as the responsibilities of FIs with respect to remediation in situations where an FI has contributed to an adverse human rights impact (see box below).

Non-exhaustive examples include:

- Whether the bank’s actions and decisions on their own were sufficient to result in an adverse human rights impact, without the contribution of clients or other entities

- Whether the bank was incentivising harm

- Whether the bank was facilitating the harm (such facilitation exists when an FI knows or should have known about human rights risks associated with a client, project, or investee company, and mitigation or preventive actions were insufficient)

- The quality of a bank’s human rights systems and its human rights due diligence processes.

Further information can be found in the UN Human Rights’ Response to Request from BankTrack for Advice Regarding the Application of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in the Context of the Banking Sector.

Further, the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct highlights several factors to be considered in determining whether a company’s – or FI’s – actions or inactions could be deemed to have contributed to an impact in a specific case. These factors include:

- The foreseeability of a particular impact

- The degree to which an activity increased the risk of an impact occurring, and

- The effectiveness of mitigation measures in reducing the risk of impacts occurring.

The quality and effectiveness of an FI’s due diligence process, or shortcomings in that process, therefore play a role in the analysis of these factors. Where an FI has not undertaken appropriate human rights due diligence, it may miss risks and omit to take the steps necessary to prevent or mitigate these risks. Equally, FIs can avoid contribution through improving their due diligence to identify and address risk, and ensuring robust mitigation measures to prevent adverse impacts are in place as a condition of finance. Although FIs will in the majority of cases be ‘directly linked’ to adverse impacts caused by their clients, in some cases they may also contribute to adverse impacts if their activities cause, facilitate or incentivise their clients to cause harm. This can happen, for example, when an FI has taken a specific action or made an omission that motivated or encouraged a client to cause harm, beyond provision of the lending service; practical examples of this happening in the context of general corporate lending are scarce.

Normally, for an FI to facilitate an adverse impact through corporate lending, there would have to be some action or omission by the FI that enabled or made it easier for a client to cause harm, in addition to the provision of the lending service itself. In practice, an FI is less likely to contribute to an adverse impact through incentivisation than through facilitation (see for example OECD, Due Diligence for Responsible Corporate Lending and Securities Underwriting). Further, in the context of project finance, OECD guidance on Responsible Business Conduct Due Diligence for Project and Asset Finance Transactions sets out those adverse impacts which financial institutions may contribute to or may be directly linked to through their clients or other business relationships in the context of project or asset finance. Note that, recognising that an FI can in principle contribute to adverse human rights impacts through financing does not shift the burden of responsibility from the client / investee causing the impact onto the FI, and the FI’s client / investee retains its own responsibilities under the UNGPs.

Taking steps to ensure that other parties meet their responsibilities in relation to remedy does not mean the FI is accepting responsibility for remedy itself. Although there might be expectations in some situations for the FI to provide remedy where the other parties do not. Existing guidance acknowledges that the assessment of whether an FI is contributing to an actual or potential adverse impact caused by a client is a complex exercise (see, for instance, OECD, Due Diligence for Responsible Corporate Lending and Securities Underwriting). In practice, there is a continuum between ‘contributing to’ and having a ‘direct link’ to an adverse human rights impact: an FI’s involvement with an impact may shift over time, depending on its own actions and omissions. For example, if an FI identifies – or is made aware of – an ongoing human rights issue that is directly linked to its operations, products or services through a client / investee relationship, yet over time fails to take reasonable steps to seek to prevent or mitigate the impact, it could eventually be seen to be facilitating the continuance of the situation and thus be in a situation of ‘contributing.’ Such reasonable steps could for instance be: bringing up the issue with the client’s / investee’s leadership or board, persuading other FIs to join in raising the issue with the client / investee, or making further financing contingent upon correcting the situation.

Further reading

- Dutch Banking Sector AgreementWorking Group – Enabling Remediation

- Equator PrinciplesTools to Enhance Access to Effective Grievance Mechanisms and Enable Effective Remedy

- OECDOECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct

- OECDExpert letters and statements on the application of the OECD Guidelines and UN Guiding Principles in the context of the financial sector

- OECDResponsible business conduct due diligence for project and asset finance transactions

- OECDDue Diligence for Responsible Corporate Lending and Securities Underwriting

- UN Human Rights Response to Request from BankTrack for Advice Regarding the Application of the UN

- ShiftFinancial Institutions and Remedy: Myths and Misconceptions

- ShiftRethinking Remedy and Responsibility in the Financial Sector. How using an ecosystem approach can push the remedy conversation out of deadlock and into meaningful action

- BankTrack & OxfamDeveloping Effective Grievance Mechanisms in the Banking Sector