Table of Contents

Once human rights impacts and risks are identified, an FI should take action.

Where it is necessary to prioritise actions to address actual and potential adverse human rights impacts, FIs should first seek to prevent and mitigate those that are most severe or where delayed response would make them irremediable. Identifying these salient human rights issues is meaningful within the framework of the UNGPs as long as it leads to concrete actions.

The type of action will depend on how the FI is involved with the human rights impacts – namely, through a) causing adverse impacts, b) contributing to adverse impacts caused with or through another entity; or c) being directly linked to adverse impacts through business relationships. The appropriate action will vary according to the extent of an FIs leverage in addressing the adverse impact.

|

Cause |

An FI can cause an adverse impact where its activities (its actions or omissions) on their own ‘remove or reduce’ a person’s (or group of persons’) ability to enjoy a human right, i.e. where the FI’s activities alone (without those of clients or other stakeholders) are sufficient to result in the adverse impact. In the context of an FI’s activities, ‘cause’ is most likely to arise in the context of bank’s own employees or consumer banking, for instance if an FI discriminates against a particular employee or customer on the grounds of ethnicity or religion. |

|

Contribute |

An FI can contribute to an adverse impact through its own activities (actions or omissions) – either directly alongside other entities (contribution in parallel), or through some outside entity, such as a client (contribution through a third party). Contribution may occur when an FI facilitates or incentivises human rights abuses or in cases where an FI fails to use its leverage or conducts insufficient human rights due diligence. For example, an FI that provides project financing despite the fact that it knew or should have known that displacement was a risk, yet took no steps to ensure that the client prevented and mitigated the risk and resulting impact. Contribution may also occur in cases where an FI and its cofinanciers insist on project financing timelines which do not allow for sufficient stakeholder consultation, which is then linked to resulting adverse impacts on rightsholders. |

|

Direct linkage |

Direct linkage refers to situations where an FI has performed adequate human rights due diligence and has not caused or contributed to an adverse impact, but there is nevertheless a direct link between the operations, products or services of the FI and an adverse impact. A situation of ‘direct linkage’ may occur where an FI has provided finance to a client and the client, in the context of using this finance, acts in such a way that it causes (or is at risk of causing) an adverse impact. For example, an FI provides a corporate loan to a company that buys and trades minerals from suppliers in a conflict area, and the proceeds from sales of these minerals in that area are alleged to fund the activities of armed groups involved in human rights abuses. |

Broadly, in cases where a financial institution is causing or contributing to actual adverse impacts it should take necessary steps to cease or prevent its own contribution, use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impacts to the greatest extent possible, and provide for or cooperate in the remediation of the impacts through legitimate processes.

Where the financial institution is found to be directly linked to actual or potential adverse impacts related to a finance transaction, but has not contributed to the impact, it should use its leverage with clients (or project sponsors) to seek to prevent and mitigate the impacts, which can include encouraging remediation. Importantly, the FI’s relationship to harm is dynamic. It may change based on the situation as well as the level of due diligence measures undertaken.

In the context of the UNGPs, levearge refers to the ability of a business enterprise to effect change in the wrongful practices of another party that is causing or contributing to an adverse human rights impact.

If a bank has leverage to prevent or mitigate an adverse impact, it should exercise it. This may include using leverage to influence relevant parties to provide remedy (also known as ‘enabling remedy’). If it lacks leverage, there may be ways to increase it, including by working with other FIs or businesses. In cases where the bank lacks leverage to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts and is unable to increase its leverage the bank should consider ending the relationship, taking into account credible assessments of the potential adverse human rights impacts of doing so. This is discussed further in the context of ‘Resonsible Exit’ (see below).

Further reading

- ShiftUsing Leverage With Clients To Drive Better Outcomes For PeopleResource capturing key takeaways from the Financial Institutions Practitioners Circle, and a list of actions that FIs can put into practice.

- ShiftTackling Modern Slavery through Financial Sector LeverageBriefing Paper focusing on responsible lending and investment practices, exploring what guidance, tools and solutions are available to financial sector actors seeking to lend and invest in ways that reduce modern slavery and human trafficking risks.

Key principles and guiding questions

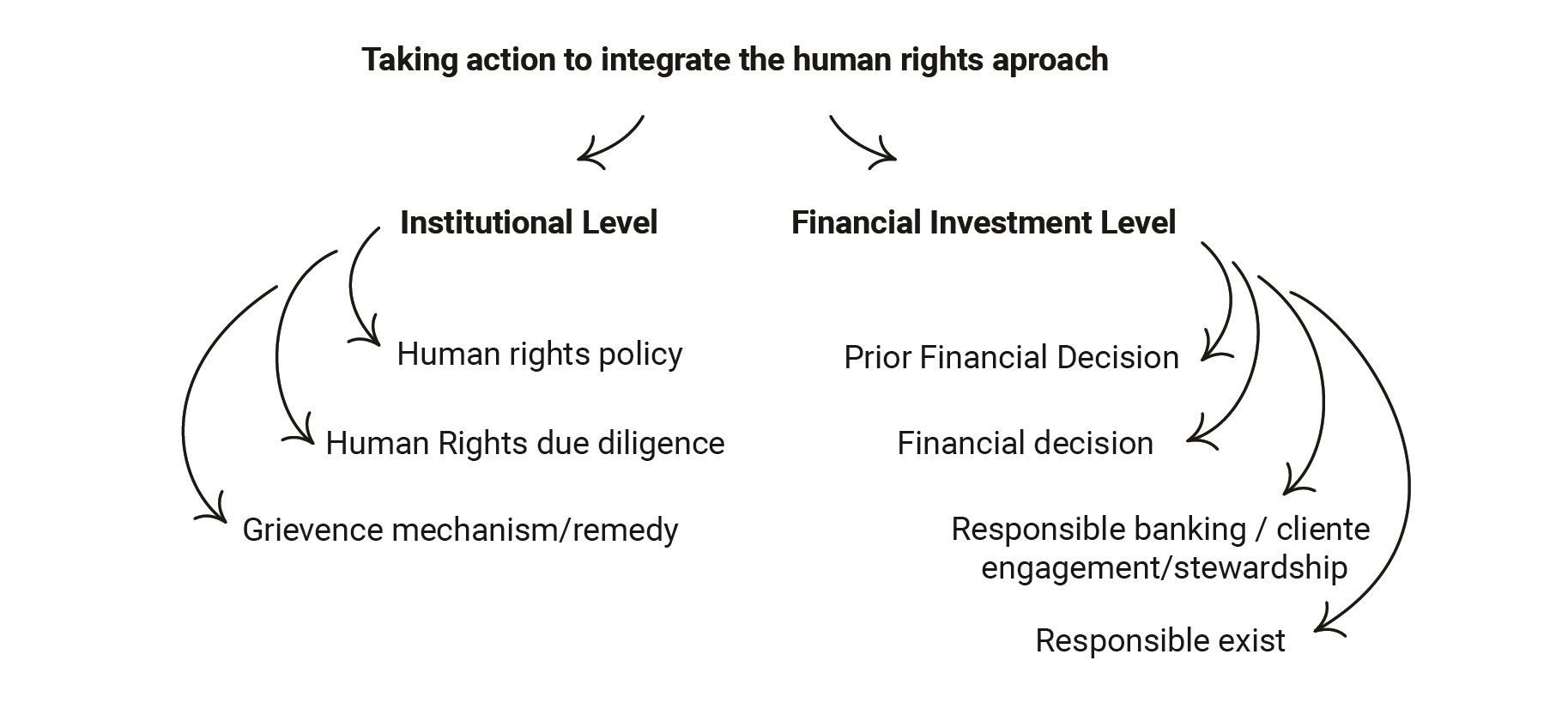

When human rights risks are identified, appropriate measures can take place either at institutional level or at the financing level throughout the different stages of the transaction cycle (activities prior to financial decision-making, financial decision-making, responsible financial / investment stewardship, responsible divestment).

At the institutional level, measures may involve strengthening human rights policies, sectoral policies, improving processes for risk identification and management, or enhancing mechanisms for access to remedy. At the specific financing / investment level, measures may include the implementation of specific client engagement plans, or the inclusion of contractual clauses.

- Do institutional policies and processes address use of leverage and mitigating impacts?

- How are clients engaged in relation to human rights issues? How can leverage be built during early stages of the relationship?

- To what extent do client contracts integrate human rights related requirements?

- How are human rights related plans, actions, or mitigation developed for transactions which give rise to human rights risk? How frequently are these mitigations developed and by whom?

- How are stakeholders involved when designing and implementing mitigation measures?

- Are there opportunities to collaborate with peer FIs in order to increase leverage or implement mitigation measures?

- What training can be provided to both internal teams and clients in order to build leverage and improve the design and implementation of mitigants?

- How do we use leverage, monitor, disclose, communicate, and evaluate mitigation efforts?

- Do we have the capacity/resources to manage the level of risk to people associated with this client or transaction?

Taking action: steps and measures

The following sections specifically explore the concept of “taking action” and mitigation in connection with financing operations, including equity investments, corporate lending and project finance. This toolkit does not prescribe specific actions banks can take, as that will be context specific, however it suggests some potential steps and measures that can be considered.

The steps and measures elaborated below are also addressed in the sector modules which address actions with a sector specific lens.

The results of the Human Rights Screening and Risk Assessment should indicate whether an FI’s policies are adequate to manage identified impacts. An FI can also consider, for instance, developing specific policies and procedures for sectors, regions and/or business models that have been found to give rise to particularly salient risks within the FI’s portfolio, including setting out expectations and requirements for addressing human rights risks on these sectors / regions /business model during all finance stages. Specifically, FIs should incorporate findings from HRDD into policy updates to address any identified gaps or areas needing improvement, as well as using feedback from stakeholder engagement to inform policy revisions. It is also important to ensure enough resources, internal capacity and training for the proper implementation of FI policies (addressed in further detail below). Further information on policy development can be found in the section on ‘Policy commitments and human rights‘.

FIs should consider the risks and characteristics specific to their portfolio in order to improve and strengthen existing risk screening, management and monitoring systems, to enhance the institution’s ability to deliver on their human rights commitments. For example, this might include:

- Integrating sector and / or region-specific human rights risks into tailored due diligence questionnaires, credit and risk assessments, and monitoring templates and reports.

- Improving human rights risk assessment processes by utilising data from past HRDD to refine risk indicators and assessment criteria.

- Setting up efficient internal information-sharing mechanisms to allow for human rights risks identified to feed into the overall management system, including information infrastructure (such as shared sectoral / regional risk registers or databases) and defined responsibilities (such as “issue owners” for particular risk areas).

- Ensuring adequate in-house (and /or third-party) capacity to undertake human rights risk assessment.

- Focusing on client specific risk factors, such as past performance or track record, media reports, government findings, or third-party assessments on human rights violations associated with previous activities, known instances of human rights infringements by the client / investee company, for instance in relation to human rights defenders or through the use of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs).

- Not relying solely on ratings agencies’ reports, but also looking into leading indicators of potential impacts, such as risks associated with certain business models and analysing the capacity of higher risk clients to manage impacts. This could include an assessment of the client’s leadership and governance approach, whether it has identified its own salient issues, and whether it conducts stakeholder engagement.

- Enhancing systems to ensure early identification of the presence of vulnerable groups, such as Indigenous Peoples and other vulnerable minority groups, women and girls at risk of GBVH, communities and local stakeholders vulnerable to impacts arising from climate change and environmental degradation.

Good client / investee engagement can create opportunities to build and use leverage by ensuring a common understanding between FIs and clients of human rights risks, gaps, and required actions, ensuring that measures are adequate and appropriated. The client / investee engagement checklist, provided here (PDF), offers tips and pointers on client engagement. Overall, it is important for FIs to identify opportunities for leverage at an early stage. When and how to build leverage at an early stage will depend on financing modalities. For example, while engagement can be relatively direct in the context of private equity (e.g. through board seats or Limited Partner Advisory Committees) or project finance, engagement in the context of public markets may take the form of shareholder proposals (or indirectly through proxy voting guidelines which reflect human rights principles) or stewardship. Examples of engagement opportunities according to type of financial operations are provided below.

| Asset / financing modality | Identifying early opportunities for leverage |

|

Private equity investments |

|

|

Public equity investments |

|

|

Project finance |

|

|

Debt finance / fixed income Corporate lending |

|

Further reading

- Working Group on Business and Human Rights Investors, environmental, social and governance approaches and human rightsReport exploring the responsibility of investors under the UNGPs as well as the opportunities for aligning ESG approaches with international human rights due diligence standards

- OECDDue Diligence for Responsible Corporate Lending and Securities UnderwritingGuidance aimed at banks and other financial institutions, specifically in the context of corporate lending and underwriting, including recommendations on leverage

- OECDResponsible business conduct due diligence for project and asset finance transactionsGuidance aimed at banks and other financial institutions, specifically in project finance and asset finance transactions, including recommendations on leverage

- OECDResponsible business conduct for institutional investorsGuidance aimed at institutional investors, specifically in investment portfolios. Including recommendations on leverage

Although dependent on the mode of financing, contractual requirements are a common tool to build (or contribute to building) leverage, and FIs should consider integrating human rights considerations into contractual clauses based on organisational human rights policies and commitments (see section on ‘Policy commitments and human rights’). This may include specific requirements on clients / investees to develop appropriate management systems, such as human rights due diligence systems, the development of which can be a precondition for disbursements.

As an example, the OECD outlines practical steps to incorporate responsible business conduct (RBC) expectations into contractual documents or other written statements/commitments with prospective clients in the context of corporate lending:

- Requiring clients to put responsible business conduct management systems in place or meet specified international standards or conditioning disbursements on a verification of specified environmental and social conditions

- Requesting client consent for waivers of confidentiality of the client’s relationship to the bank where relevant

- Providing prospective clients with incentives to meet certain RBC related targets (e.g. coupling the interest rate of the loan with the company’s sustainability performance).

Further reading

- De Boer, Wilke and Scheltema, MartijnHuman Rights Provisions in General Corporate LendingRecommendations for banks to build on practice of ‘sustainability linked loans’ by including predetermined sustainability targets focused on human rights, including guidance for human rights provisions in loan agreements, based on standard loan market (LMA) documentation

- Equator PrinciplesGuidance For EPFIs On Incorporating Environmental And Social Considerations Into Loan DocumentationGuidance Note providing an overview of the Equator Principles and their applicability to certain financial transactions and services, along with template contractual provisions for Equator Principles Financial Institutions (EPFIs) to refer to in connection with, and adapt for use in, financing agreements

To require and incentivise clients / investees to integrate human rights considerations into their management systems, FIs can support clients / investees in the development of mitigation plans, and agree on timelines as well as specific actions. Policies and practices should be regularly reviewed and updated based on lessons learned and feedback from stakeholders.

In some financial operations, environmental and social action plans (ESAPs) are an important and common tool for developing specific mitigants in response to risks. When developing ESAP items, it should be ensured that actions are both realistic (i.e. implementable) while also being responsive to identified human rights risks. Certain criteria or principles can guide the drafting process:

- Action plan items should be as specific as possible and all items should supported by objective or clearly measurable monitoring indicators (see section on ‘Monitoring‘).

- Action plan items should include indication of resource requirements or effort

- Action plan items should be time-bound based on reasonable implementation timelines

- Specific roles or individuals should be accountable for the implementation of each item.

Consequences for failing to address action plan items should be clearly communicated. While human rights risks can typically be addressed as part of broader E&S actions, there may be cases where the development of specific additional plans are required, e.g. where greater risks are identified. It is recommended that plans are developed by individuals or consultants with specific expertise. None of these plans needs to be conducted as stand-alone exercises, ideally and when possible they will be developed as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment and respective Environmental and Social Management Plan or equivalent. Examples of different impact assessments and actions plans, accompanied by descriptions and resources, can be found here (PDF). Additionally, further resources and guidance on sector-specific mitigation considerations can be found in the sector profiles.

When human rights risks are identified, the expectation is that FIs avoid any actions or omissions that could facilitate or encourage them. Actions which seek to avoid facilitating or incentivising human rights abuses (either through acts or omissions) requires a firm understanding of human rights risks and will vary based on investment context. Appropriate actions might entail:

- Ensuring that key procedural requirements are met prior to providing financing or disbursing. This could include ensuring that stakeholder consultation has been undertaken or free prior and informed consent (FPIC) has been obtained.

- Ensuring that disbursements or financing are predicated on the adequate development and implementation of corrective action plans (see section on ‘Action plans and specific mitigations’ above).

- Reviewing project / investment timelines and budget to ensure that human right risk identification and planned mitigation approaches can be carried out / have been carried out. This can involve ensuring that timings and budget allow for robust studies / assessments to be undertaken, as well as ensuring that project timelines do not create pressure on workers or other rightsholders (e.g. cases where short project implementation timelines negatively impact working hours, rest periods, or health and safety outcomes).

Wherever possible, such measures should be developed in collaboration with stakeholders and integrated into contractual requirements (see section on ‘Stakeholder engagement‘).

Human rights risks are often rooted in complex social, cultural, and economic dynamics. Some human rights risks and impacts may, by their nature, require systemic solutions. Relevant factors might include prevailing societal attitudes which reflect patriarchal or discriminatory norms, poor legal or enforcement frameworks, fragile security situations, and pervasive informality.

These realities do not discharge the financial sector of its obligation to respect human rights. However, in the context of systemic issues, financiers, projects, or client / investee companies can seek to mitigate impacts and address risks through collaborative efforts or partnerships. Effective collaboration and partnerships can amplify leverage, raise awareness, and allow for coordinated action in response to challenging issues. Examples include:

- Industry or sector-based initiatives with relevant human rights focus or working groups

- State-led human rights multi-stakeholder initiatives

- International or supra-national led multi-stakeholder initiatives.

FIs can enhance transparency and disclosure practices by providing stakeholders with access to relevant information about investments and loans, including potential human rights impacts, mitigation measures, and grievance mechanisms. Client / investment-specific disclosures will require the FI to obtain (ideally at the outset of the relationship) the consent of the client / investee to disclose specific information – such as the existence of the client / investee relationship with the FI.

FIs can also publicly report against clear human rights indicators, including salient issues, measures, and results, including a detailed account of HRDD processes, findings, actions taken, and outcomes. Collaborating with clients / investees can involve designing communication and transparency strategies which go beyond sustainability reporting, such as field meetings with communities and key stakeholders. Further information can be found in the section on ‘Communicating and disclosing‘.

In order to meet human rights obligations, FIs need to have the necessary in-house (and / or third-party) capacity to undertake human rights risk assessment and client / investee engagement. This may involve investment in building internal expertise on human rights, including appointing dedicated staff, as well as providing continuous professional development opportunities to stay updated with emerging trends and challenges.

FIs can provide training and capacity-building programs for FI staff and relevant stakeholders on human rights issues relating to their investment and lending activities, including the identification, prevention, and mitigation of human rights violations in the context of investments in the identified high-risk sectors and /or regions. This can include case studies and lessons learned from past HRDD to highlight practical implications and best practices.

FIs can work with clients / investees to establish robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to track the effectiveness of prevention and mitigation measures. Policies and practices should be regularly reviewed and updated based on lessons learned and feedback from stakeholders. At the client / investee level, consistent company-wide tracking of indicators linked to the most salient human rights impacts should be accompanied by regular engagement with stakeholders. Further information can be found in the section on ‘Monitoring‘.

Grievance mechanisms

FIs should ensure that accessible and effective grievance mechanisms are in place to enable affected stakeholders to raise concerns and seek redress for any alleged negative human rights impacts related to their investment or lending activities. This requires evaluating grievance mechanisms at FI level to ensure that third-party claims are captured, including those impacted by the activities of portfolio companies (e.g. workers, communities, or commercial partners).

FIs should also require and support clients / investees to adopt effective access to remedy mechanisms at the project / operational level. It is vital to ensure that all workers, including contractor and subcontractor workers, and other affected stakeholders, have access to a safe and effective grievance mechanism at the operational level, free of reprisal risk, both as a means of identifying risks of adverse impacts to these workers and affected stakeholders early on, and to provide a route to remedy.

Further information is provided in the section on ‘Grievance‘.

Remedy

Where negative human rights impacts have occurred, remedy describes the processes and outcomes which can counteract or ‘make good’ the negative impact. It can take various forms including apologies, restitution, rehabilitation, compensation, or guarantees of non-repetition.

Financial institutions have a key role to play when negative human rights impacts occur and remedy is required. This might entail:

- Providing for and cooperating in remediation where FIs cause or contribute to adverse human rights impacts

- Enabling remedy, including using and building leverage with clients / investee to enable remedy before and after harms have occurred, in the case of linkage to impacts.

Actions which are available to FIs will depend on the investment context and financing modality, but encompass activities which should be undertaken before and after impacts occur, all of which should be based in stakeholder engagement. Further information can be found in the section on ‘Remedy‘.

| Before impacts occur | After impacts occur |

|

|

While disengagement should be considered as a last resort, responsible exit may be an option under certain conditions when an FI lacks sufficient leverage to change the investee / client’s conduct or is unable to increase leverage. Consistent with the UNGPs, FIs are expected to identify and mitigate any adverse impacts associated with exiting an investment / loan, or ending a business partnership.

International human rights standards do not seek to prohibit investments which involve difficult human rights challenges. The UNGPs and other standards provide a human rights due diligence framework which should allow banks to identify and address negative human rights impacts. Seeking to exit when faced with human rights challenges may be counterproductive in cases where the continuation of a financial relationship can allow for exercise of leverage to mitigate human rights impacts and enabling remedy (see also section on ‘Remedy‘). There may, however, be cases where disengagement or divestment is might be expected. According to the UNGPs:

There are situations in which the enterprise lacks the leverage to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts and is unable to increase its leverage. Here, the enterprise should consider ending the relationship, taking into account credible assessments of potential adverse human rights impacts of doing so.

For financial institutions, it may be necessary to consider divestment or disengagement in relation to investees that have chronically underperformed in relation to their human rights obligations and further mitigation is not a possibility. In other cases, a decision to divest or disengage might be attributed to broader contextual factors, such as the deteriorating human rights situation in a particular country, region, or sector. Guidance on key factors to consider prior to exit, implementation principles, and further resources are included here (PDF).

Further reading

- UN Human Rights Business and Human Rights in Challenging Contexts: Considerations for Remaining and ExitingSummary of key considerations for businesses when evaluating the appropriateness of exit in light of difficult or challenging human rights contexts

- SOMOShould I stay or should I go? Exploring the role of disengagement in human rights due diligenceDiscussion paper exploring the concept of disengagement in the context of human rights due diligence

- OECDGlobal Forum on Responsible Business Conduct: Session Note, Responsible disengagementNote that summarises high level disengagement principles as well as sector specific case studies

- UN Human Rights Remedy in Development Finance: Guidance and PracticeChapter V contains a detailed discussion of key principles relating to ‘responsible exit’ and emerging developments in the context of development finance

- CAOResponsible Exit: Discussion and Practice in Development Finance Institutions and BeyondResource that explore and aggregates responsible exit practices from a range of institutions, including the preparation, design, and execution of responsible exit

- GIINLasting Impact: The Need for Responsible ExitsOverview of theory and approaches to responsible exit, particularly in the context of impact investing